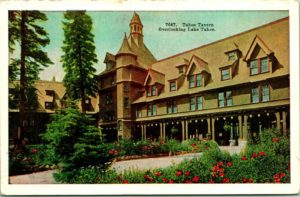

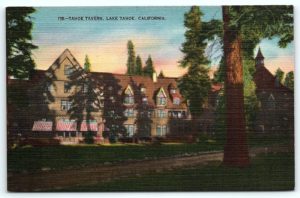

The original Tahoe Tavern was an internationally famous and elegant mountain resort built in 1901. The luxurious accommodations and amenities, such as the casino, ballroom, and pleasure pier, drew San Francisco Bay society.

Enjoy the 50th Anniversary historical telling of Tahoe Tavern Properties, featured in Tahoe Weekly magazine and written by Mark McLaughlin.

The Tahoe Tavern condominium properties located south of Tahoe City is celebrating its 50th anniversary this summer as the reincarnation of the original Tahoe Tavern Hotel & Casino built at the turn of the 20th Century. The contemporary version of the Tahoe Tavern was mostly completed in 1965, but before we look into that story, let’s revisit the visionary efforts of Duane L. Bliss, the man who built the Tavern and singlehandedly established modern tourism at Lake Tahoe.

Duane Leroy Bliss was a man of integrity, ability and vision; positive character traits that would manifest themselves at Lake Tahoe. Born in Savoy, Mass., in 1833, Bliss completed his schooling by age 13. Tragically, this accomplishment was quickly followed by his mother’s death, so he signed up for a two-year stint working as a cabin boy on a ship traveling to South America. He returned home in 1848 to teach in a Savoy school, but the following year, news of the Gold Rush swept New England. Bliss quit his job and boarded a California-bound steamer.

Duane Bliss was barely 17-years-old when he reached California in 1850, but with hard work he made money on a small mining claim. He used his earnings to acquire interest in a general store and hotel in Woodside on the San Francisco Peninsula. Over the next decade, he gained much-needed business experience and in 1860 Bliss moved to Gold Hill, Nev., where he was hired to manage a quartz mill at Silver City. The Comstock mining excitement was in its infancy and the men who controlled capital would soon control the land, as well as the logging and mining industries that were just getting started.

Over the next eight years, Bliss tried his hand at all aspects of Comstock industry. He supervised large construction projects, ran mining and ore milling operations, and held executive banking positions. By the time Bliss was 30-years-old, he had earned a reputation for his sound judgment and strong, ethical principles.

Bliss became a partner and manager for a Gold Hill banking firm, but the company was acquired by the Bank of California. The bank’s directors were ruthless when it came to gaining control of Nevada’s mining operations. They used low-interest loans to leverage takeovers of money-strapped mine and stamp mill operators. But Bliss wasn’t out of a job. The hard-nosed executives at the San Francisco-based Bank of California knew that they were held in low esteem by Comstock communities. But Duane Bliss was well known for his honesty and good standing in western Nevada, so the bank retained him as chief cashier.

In 1868, the Bank of California initiated the construction of the Virginia & Truckee Railroad, and they appointed Duane Bliss as right-of-way agent, responsible for acquiring the necessary properties for the project, as well as enticing investors. D.L. Bliss wasn’t being a stooge for the hated bank; he was in the process of obtaining forestland in the Tahoe Basin. Bliss realized that the valuable timber needed to sustain Comstock mining operations was located on the slopes surrounding Lake Tahoe, and the new V&T railroad would economically transport it to Virginia City.

In 1873, Bliss and a group of investors formed the Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company with Bliss as president, general manager and largest stockholder. The company had three divisions: logging, wood milling and railroad transportation, with its center of operations at Glenbrook on Lake Tahoe. Over the next quarter century, this consortium removed most of the old growth timber in the Tahoe Basin. It was a massive amount of wood – nearly 750 million board feet of timber, and 500,000 cords of firewood. At one point, the company owned nearly 80,000 acres, including miles of pristine Tahoe shoreline. Bliss had purchased much of the land for as little as $1.25 an acre. Famed Virginia City journalist Dan De Quille said it best: “The Comstock Lode was the tomb of the forests of Tahoe.”

By 1880, mounting damage to the Tahoe forest drew protests from visitors, newspaper editors and politicians. A movement toward mitigating exploitation of Tahoe timber gathered popular support. Duane Bliss ordered loggers on his timber tracts to spare all trees under 15 inches in diameter in order to protect a portion of the forest and accelerate its eventual re-growth.

Eventually, the Comstock went bust for good. The local economy collapsed and people deserted the region in droves. When the dust finally settled, it was apparent that the clear-cut logging operations had decimated much of the region’s natural beauty. At the south shore of Lake Tahoe, abandoned logging camps, empty flumes, rusting railroad equipment and silent mills haunted the denuded landscape.

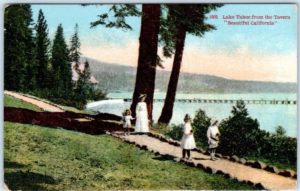

But Duane Bliss wasn’t giving up on the magic of Lake Tahoe. He realized that the lake had everything to support world-class tourism and he had a vision for how that would happen. His scheme required three interrelated projects – a stylish passenger steamship, a railroad to connect Tahoe City with Southern Pacific’s transcontinental line in Truckee, and the Tahoe Tavern, a luxury hotel.

Bliss started with the “SS Tahoe,” a 169-foot-long beauty that he launched in June 1896. This elegant watercraft was built for comfort and capable of carrying 200 passengers, plus mail and freight. The sleek steel hull was comprised of eight, watertight compartments, which made the ship virtually unsinkable, and with a top speed of 18 knots, she could circle Lake Tahoe in less than eight hours with stops. Known fondly as “The Queen of the Lake,” she would transport thousands of passengers over nearly 45 years of service.

To facilitate easier access to North Lake Tahoe, Bliss built a narrow gage railroad from Truckee to Tahoe City. He formed the Lake Tahoe Railway & Transportation Company with all of its capital stock held by members of his family. Duane appointed his oldest son, civil engineer William Seth, to survey the proposed railroad route along the Truckee River. Unlike previous logging railroads in the region, his was purposed toward tourists. It operated from May 15 to Nov. 15 and visitors comprised the bulk of its business.

The centerpiece in the Bliss plan was the Tahoe Tavern Hotel & Casino, which opened in mid-1902. Designed by another Bliss son, Walter, it was considered the finest hotel between San Francisco and the Rockies.

The first Tahoe Tavern opened in the spring of 1902 as part of timber baron and railroad operator Duane L. Bliss’ grand scheme to elevate Tahoe Basin tourism. Bliss integrated a sleek, stylish passenger steamship and a narrow gage train system to cater to the comforts of well-heeled visitors heading to Lake Tahoe from the United States and Europe.

The luxurious hotel, designed by Duane’s son, architect Walter D. Bliss, was grand enough to be considered the finest hostelry between San Francisco and the Rockies. In addition to many landmark San Francisco buildings, Walter also designed the Hellman-Ehrman Mansion at what is now Sugar Pine State Park on Tahoe’s West Shore. Duane Bliss financed the project by mortgaging his short line railroad in order to acquire a $500,000 loan. It was a shrewd investment as the resort’s receipts repaid the borrowed money back many times over.

In 1905, a promotional pamphlet described the Tahoe Tavern as “a long rambling building of shingles the color of pine bark, with 20-foot porches and supports of rough-sawed native wood, all set in a primeval forest.” The top of the three-story building included many gables on a steeply pitched roof to shed winter snow. The interior featured beamed ceilings with elk horn chandeliers and simple rustic furniture. Rooms were furnished with “perfectly appointed baths, large closets, electric lights, steam heat and running water.” Diners were served the best foods available, including perfectly prepared Tahoe lake trout. For those conducting business or wishing to contact the outside world, telephone and Western Union Telegraph service was available. Hotel rates started at $3 per day.

Unlike the Bliss’ more formal Glenbrook Inn, which required shirt ties at dinner, the Tahoe Tavern was much more casual. In his 1915 classic “Lake Tahoe: Lake of the Sky” historian George Wharton James described life at the Tavern.

“It is not a fashionable resort,” he wrote, “in the sense that everyone, men and women alike, must dress in fashionable garb to be welcomed and made at home. Rather the Tahoe Tavern is the most wonderful combination of primitive simplicity with twentieth century luxury.” James added: “If one has taken a walk in his white flannels he is welcome to dance at the dining-room or social hall. If one comes in from a hunting or fishing trip at dinner time, he is expected to enter the dining room dressed as he is.”

By the 1930s, however, the resort’s dress code for lunch and dinner became more formal with a dress and heels required for women and coat and ties for men.

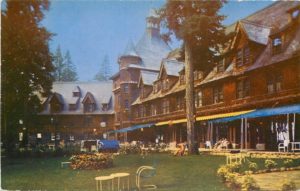

Testament to the myriad of outdoor activities available at Lake Tahoe, visitors were encouraged to “bring their old clothes so that they may indulge in mountain climbing, bicycle riding, rowing, fishing, horseback riding, botanizing in the woods or any other occupation where old clothes are the only suitable attire.” For those wishing a more relaxing experience, the large lawn between the hotel and the lake was peppered with swing sets and reclining chairs that looked out over Big Blue.

The Tavern was such a successful tourist magnet that in 1906 an 80-room annex was added along with a gambling casino, barbershops and spacious ballroom. On Dec. 23, 1907, family patriarch Duane Bliss died after a brief illness. The loss was felt well beyond the family as one obituary confirmed: “His death will be a profound loss to both Nevada and California, for his business interests were interwoven in both states and his sterling manhood was something to rest on.”

The Bliss tourism dynasty continued to grow after Duane’s death. More additions to the Tahoe Tavern complex included a physicians’ office, a laundry, as well as a modern steam plant and water system. Piped in potable water came from the Burton Creek drainage on the other side of Tahoe City because steamer and boat traffic on the lake polluted the shoreline water near the hotel. By 1909, the resort could accommodate 450 guests. Another wing was added to the hotel in 1925 for $250,000 and the casino acquired a well-stocked liquor bar.

Automobiles took the country by storm in the early years of the 20th Century. Eventually, the popularity of the new form of transportation would meaningfully impact both steamer and train traffic at Lake Tahoe, but in the spring of 1911 the Tahoe Tavern offered a large silver trophy for the first party to drive a car from California over Donner Summit to the hotel. Management hoped to ramp up its early season tourist business and to generate advertising headlines in the San Francisco newspapers. Although promoters at the Tahoe Tavern were calculating that their trophy would be won by a socially prominent person from the Bay Area, the primary contender turned out to be a group of men from the Grass Valley area led by Arthur B. Foote.

Foote’s group wasn’t the only one competing for the prize, but they took a commanding lead in the deep June snowpack. By June 9, they had reached Soda Springs near Donner Pass where they spent the day repairing various broken parts. Finally, on June 10, they pushed and pulled their vehicle over rock and snow down to Donner Lake where they had breakfast. Taking advantage of a clear road from Truckee to Tahoe City, they reached the Tahoe Tavern that day and claimed their handsome trophy.

The Bliss family sold the Tahoe Tavern to Linnard Steamship Lines in 1926 (a subsidiary of Southern Pacific Railroad) as the popularity of the automobile reduced traffic on their Lake Tahoe Railway that delivered tourists directly to the Tahoe Tavern lobby. The purchase by Linnard and the conversion of the narrow gage railroad to standard gage by Southern Pacific Railroad led to a new era for the exclusive summer resort. The new management decided to keep the hotel open during the winter months in hopes that the rapidly growing popularity of winter sports would add a new dimension to the Tahoe Tavern’s role in the community. It almost led to Lake Tahoe hosting the 1932 Winter Olympics.

In the late 1920s, an opportunity to expand into winter sports appeared at North Lake Tahoe. After the purchase of the Tavern, the new operators decided to open the facility from December to March, in an attempt to develop a winter business. Transportation to the lake was provided by SPRR, which maintained a track from the main line in Truckee to the hotel. The train provided reliable winter access for tourists heading to Tahoe.

Both Southern Pacific and the Linnard group recognized the economic potential for operating the hotel during the normally closed winter season and preparations were made for a variety of entertainment and sports activities. Southern Pacific promoted its new winter sports operation by scheduling overnight weekend excursion trains from San Francisco, a run they called “The Snowball Special.”

Initially, the main attractions were ice skating and tobogganing near the hotel, but soon a Winter Sports Grounds was developed at a pine-sheltered slope (the current location of Granlibakken Resort) about half a mile west of the hotel. A double toboggan slide was built, and then a 65-meter trajectory jump was opened by December 1927. The jump was designed so that at the apex of their leap, skiers could see distant Lake Tahoe over the forest canopy below. Today, Granlibakken is California’s oldest ski area in continuous operation.

Before long, the Tavern’s winter sports program included skating, downhill and cross-country skiing, and exhibition ski jumping. To entertain their guests, the Tahoe Tavern hired nationally ranked ski jumpers like Norwegian brothers Alf and Sverre Engen to perform daring leaps. While working at the Tahoe Tavern, Alf and Sverre had a signature move where they hit the jump simultaneously, clasped hands in mid flight, and then broke away for the landing. These professional performances drew hundreds of spectators to the Tavern and the future for winter sports looked bright as the crowds swelled. But with no way to winterize buildings built for summer guests, over time, visitors chose other venues during Tahoe ski trips.

By the 1950s, the Tahoe Tavern had deteriorated and its upper floors were condemned as a fire trap. A portion of the wooden structure burned in the early 1960s and the parcel was put up for sale for $1 million. The valuation was low because the hotel could not make a profit, but the real value was in the land. Executives for Moana Development Corporation rightfully considered that price for 25 acres of prime lakeshore property near Tahoe City a great bargain and made the deal. This was shortly after the 1960 Winter Games at Squaw Valley and the investors realized that Lake Tahoe was becoming a popular four-season resort area.

The Tahoe Tavern condominium project was designed by Henrik Bull, a legendary ski country architect. In contrast to the original hulking hotel with a tower nearly 150-feet high, Bull designed a series of low-profile, two-story units with gently sloping or flat roofs. Snow is a good insulator that keeps in the heat during winter, and the steep pitches of the old Tavern shed snow dangerously into huge piles that sometimes lasted into late spring. The crescent-shaped groups of townhouses maximized views and eliminated the straight-line aspect of row houses. Not only was the new construction more in scale with the environment, it was part of Bull’s philosophy of “regional sensibility.”

Towering first-growth sugar pines and cedars, some 6 feet in diameter, abound on the acreage and Bull managed to fit in the condominiums without removing any of the trees. Due to dilapidated conditions, all of the old, wood structures were removed, but the existing swimming pool and 1,000-foot-long pier were renovated. Even during this current drought, the pier reaches water of sufficient depth for watercraft. Where the Tahoe Tavern once stood is now a broad expanse of open grass. Another advantage of the low-profile structures and flat or slightly sloped roofs is that condo owners further from the lake often have a view of Big Blue.

By 1960, Henrik Bull had earned a reputation as a pioneer of snow country architecture in the United States. An avid lifelong skier who embraced the sport at an early age, his building designs incorporated traditional, alpine architecture that focused on efficiency and safety in heavy snow zones. In 1954, he took a ski trip to Squaw Valley where he ran into his friend Peter Klaussen. The two had been roommates in Boston while Bull earned his architecture degree at MIT and Klaussen pursued his MBA at Harvard Business School. Klaussen bought a parcel of land in Squaw Valley from developer Wayne Poulsen and he asked Bull for an innovative house design.

The completed ski chalet was featured in an illustrated article in Sunset magazine that generated an avalanche of letters requesting the construction plans or more information. Klaussen would go on to plan the layout of Alpine Meadows ski area, as well as many other ski industry achievements, while Bull would make a career designing ski country homes and projects.

Bull’s design thumbprint may be found at many top ski resorts across the country. In the Tahoe area, he was lead architect for the original Northstar Village project, as well as Stillwater Cove in Crystal Bay. Squaw Valley ski developer Alex Cushing hired Bull to design additions to High Camp, which include the swimming pool and lagoon, skating rink and spa. The prolific architect also designed the Squaw Kids building, as well as other Squaw Village renovations.

Henrik Bull died on Dec. 7, 2013, but the Tahoe Tavern condominiums remain as a monument to the talented architect’s sensibilities and expertise. Out of all his Tahoe-based projects, the Tavern remained his favorite to the end. The residents of that community share an important legacy and heritage, more than a century of Tahoe’s colorful history.